August 5, 1862 – April 11, 1890

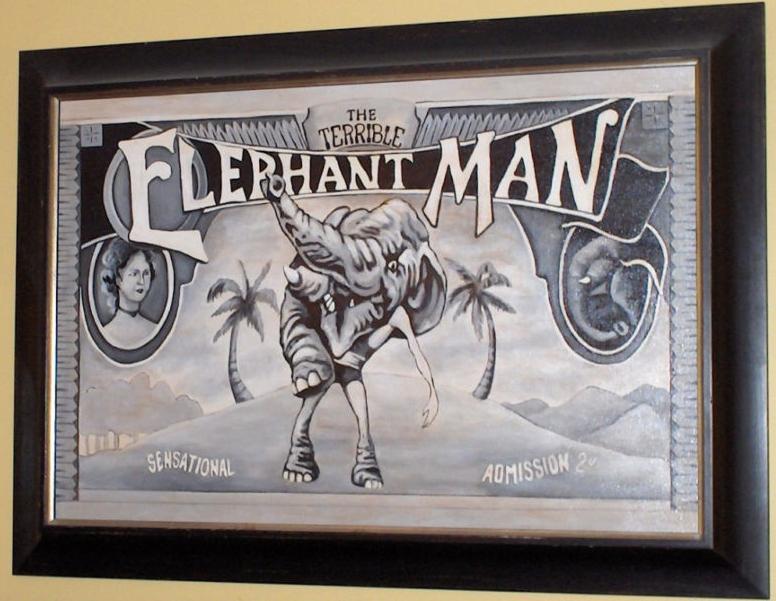

Joseph Carey Merrick was born with a disease popularly thought to be neurofribromotosis, or Proteus syndrome. Either way, he was blessed with rather unattractive growths, and his body progressively became more and more deformed. He was destined for a life of sadness and abuse, heaped on him rather generously by his family, and the public. His only success at earning a wage was to travel in “freak shows,” popular in Victorian times. One of these traveling menageries came to rest in a shop front across from the Royal London Hospital, in White Chapel Road, London.

Merrick caught the eye of Dr. Frederick Treves, a surgeon at the hospital, who paid Joseph to come across the street to be studied by students.

The menagerie traveled on. Merrick managed to save a bit of money, only to be stolen from him by the curator of the show. Merrick was stranded in Brussels. He managed to scrape together enough money for a train trip back to London, and upon his arrival at Liverpool Street Station he collapsed in exhaustion.

One hundred and twenty years later – this happened in the very same station. Coincidence? I think not.

Treves’ business card was found among his meager possessions, and a call was made to the Hospital. Treves went to claim his friend, and offered him a home within the Royal London Hospital grounds, where he would live out the rest of his life.

Treves and Merrick enjoyed a friendship, and it was Treves that took it upon himself to start referring to Joseph as “John” in his memoirs. Who knows why. For a few years Merrick enjoyed a happy life in a ground floor flat, in an area of the hospital grounds called Bedstead Square.

The entrance of Merrick’s flat has since been bricked up,

and the interiors now house the hospital catering department, but the windows out which Merrick would view the world are still there, hidden behind shelves of canned goods.

He became a celebrity, even entertaining royalty.

Regarding Merrick’s eventual demise, here is a quote direct from Treves diary: “he was found dead in his bed…He was lying on his back as if asleep, and had evidently died suddenly and without struggle. The method of his death was peculiar. So large and heavy was his head that he could not sleep lying down. The attitude he was compelled to assume when he slept was very strange. He sat up in bed with his back supported by pillows, his knees were drawn up, and his arms clasped round his legs, while his head rested on the points of his bent knees. He often said to me that he wished he could lie down to sleep ‘like other people’. I think on this last night he must, with some determination, have made the experiment. The pillow was soft, and the head, when placed on it, must have fallen backwards and caused a dislocation of the neck. Thus it came about that his death was due to the desire that had dominated his life – to be ‘like other people’.”

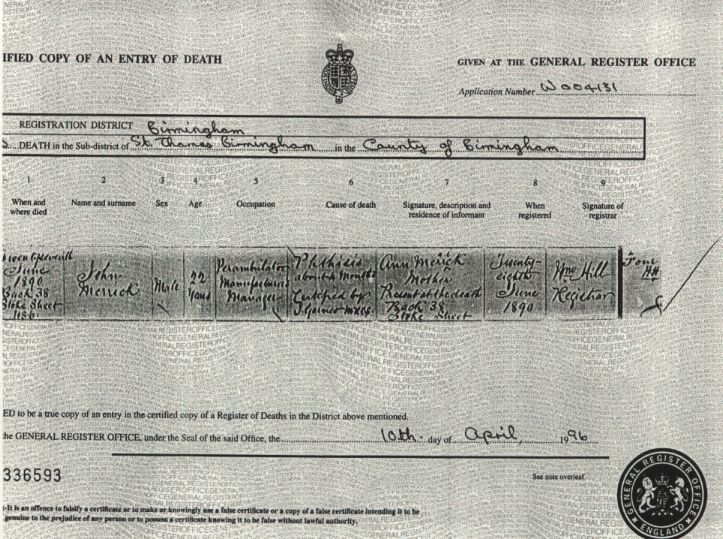

This was on April 11th, 1890. He was 27 years old.

Official Cause of Death : Asphyxia and Suffocation.

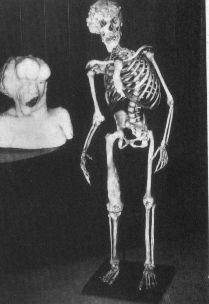

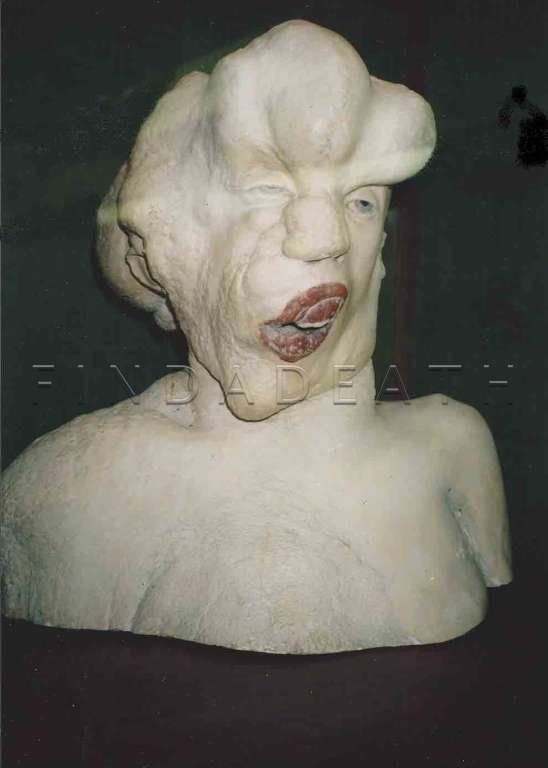

A funeral was held in the Chapel of the Hospital, and after the autopsy by Dr. Treves, it was decided that his skeleton should be set up in the Hospital Museum.

He supervised the taking of plaster casts of the head and limbs and the preservation of skin samples. To the frustration of future researchers, the skin samples were lost during the Second World War. The jars containing them dried out in the absence of staff who had been evacuated. Merrick’s assembled skeleton still resides within the walls of the hospital museum. Members of the public are not welcome.

However…

Update April 2011 – from Findadeath friend Mark Rowe:

“I usually go to London every year and on one trip, I tried to see Jospah. Prior to my trip I was in touch with a very well now forensic anthropologist who had worked with the skeleton. On his book he signed for me, he wrote, “Good Luck seeing Joseph.”

I went to the London Hospital and they turned me away immediately. I then called and asked for the pathology lab, and the bloke who answered told me the skeleton was not on public display. I then lied a bit saying that this well known forensic anthropologist told me to stop by. He said, “Oh, you know Dr. _____, do you?” I answered yes, and they let me in.

I spent an hour looking around the place. It’s like one of the teaching rooms where there are wooden bleachers and the exam table in front of them. It seemed like an old horror movie.”

So because of Mark, we can now have a color photograph (I’ve never seen one before) of Merrick’s remains, and of his death mask. Thank you so much, Mark.

Update, January 2000, thanks to Findadeath.com friend Casey for this info: Research (modern) has shown that the poor guy had Proteus Syndrome, which is extremely rare, but does exist to this day (there are fewer than 900 cases known in the world). He did not have neurofibromatosis, which is considerably more common and less disfiguring – NF causes tumors (usually small) to grow on the nerve endings, both on the skin and inside the body. It is true that for years people did blame his disfigurement on NF, but that’s been cleared up now. About one child in every 4000 is born with this genetic disease… Someone I know has it, and is President of the a chapter of the NF Foundation. The fastest way to piss off somebody who has NF is to call it “The Elephant Man’s Disease”.. trust me on that one 🙂

September 2000 – Just another update. NF (neurofibromotosis Type I) is or was called von Recklinghausen’s Disease named for my great grandfather Friedrich D. von Recklinghausen. The amount of disfigurement that Merrick experienced was finally determined to be Proteus Syndrome, some time in the late 80’s or early 90’s. – Friedrich M. von Recklinghausen

The Discovery Channel did a documentary about John, and put together a computer simulation of what he may have looked like, had he not been disfigured.

What a terrible life to be cursed with.

I can only hope he is at peace, in no pain, and no disfigurement.

R.I.P you were more of a gentleman than most peoples, truly hope u are where u belongs with angels.RV.

May he now RIP. For during his life, I’m sure he knew very little peace.