September 19, 1913 – August 1, 1970

Profile by Mark Langlois

Seattle-born Frances Farmer got herself out of a small-minded hometown only to become a commodity in the male-dominated film factory town of Hollywood. To say that strong-willed Frances bristled against the studio system is an understatement and stuff of legend thanks to numerous books and films about her life.

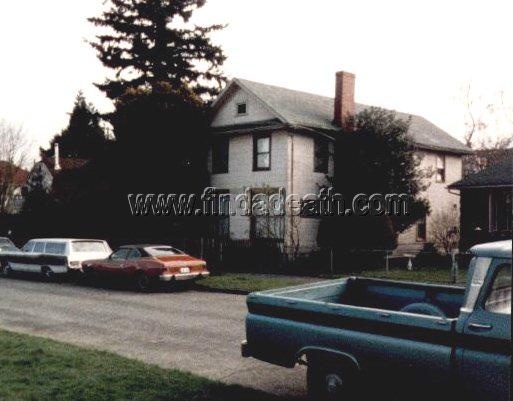

Frances grew up in this home in West Seattle. Her parents Lillian and Ernest’s marriage ended in divorce when she was a teenager. Her mild-mannered attorney father proved no match for her bossy, passionate, social activist mother.

Frances first became known as the bad girl of West Seattle when her atheistic essay won a contest from Scholastic Magazine. Her piece called God Dies made headlines (Seattle Girl Denies God And Wins Prize!) and the 18-year old Frances learned fast that she would have to plan an escape from her provincial surroundings. She got this chance as a University of WA drama student when she won a 1935 trip to Russia. When her ship returned to New York, she cashed in the return bus ticket to Seattle and sought lodging and stage work in Manhattan. Within weeks she was discovered by a talent scout and offered a 7-year contract with Paramount Studios. Frances was 22 years old.

Sunny California was a nice change from her rain swept hometown and she tried her best to follow studio orders. Frances posed for cheesecake publicity stills, controlled her weight via prescription amphetamines, and even married a handsome fellow contract player named Leif Erickson. The pretty couple settled into their home in Laurel Canyon and posed for magazine stories. Frances soon found herself co-starring with Hollywood’s biggest star Bing Crosby in Rhythm on the Range and loaned out for the Howard Hawks film Come and Get It (1936) where she was given the challenging dual roles of mother and daughter. Hawks called her “the greatest actress I have ever worked with.”

With two box-office hits under her belt and some newfound leverage, Frances started showing her true nature by defiantly refusing to attend Hollywood parties and play the glamour girl. In 1937, Frances wanted to prove herself as a dedicated stage actress. This led to a role in Broadway’s Golden Boy and a love affair with its lauded playwright – the equally married Clifford Odets. Things didn’t pan out as she hoped, and Frances found herself back in Hollywood with a broken heart and an unbroken studio contract.

By 1942, Frances was struggling with tepid film roles, impending divorce, and an addiction to Benzedrine’s and booze. She was reportedly growing more paranoid and short-tempered.

On October 19, 1942, it came to a head when she was pulled over by a motorcycle cop for driving with her headlights on bright in a wartime dim zone. Frances got mouthy and they had a scuffle. She was arrested, fined and given a suspended sentence. She paid half the $500 fine. Three months later, Frances was in no mood for a certain studio hairdresser and slugged her. With an unpaid fine and new assault charge, the police found her at the Knickerbocker Hotel on Ivar and hauled her to jail kicking and screaming for justice.

At the police station, she stated her occupation as “cocksucker”. As you do.

A judge ordered her to the screen actors Kimball Sanitarium in La Crescenta. Her mother traveled by train to California and was granted guardianship of her daughter. Back in Seattle, she and her mother battled at home and an overwhelmed Lillian had Frances committed to Western State Hospital. Wow, thanks Mom!

Western State Hospital (established 1871) is located on the site of historic Fort Steilacoom in Lakewood, WA. The facility (with its older deserted buildings now in ruins) sits on 264 acres and is the largest psychiatric hospital west of the Mississippi. This was Frances Farmer’s home for three months in 1944 and much of 1945 thru 1950. In the years that Frances was a patient at the hospital – it was reportedly very understaffed and in disrepair.

For nearly 50 years, hydrotherapy was the early treatment of choice. Wet packs, hot tubs and showers were used to calm patients. Harsher treatments of the era (later replaced with psychotropic drugs and counseling) included insulin therapy and electric shock therapy. A surgical procedure called the frontal lobotomy was used for a period of time in the 1940s as well as the simpler “trans-orbital lobotomy” performed with an ice pick like tool. Some of these procedures are re-enacted with freaky mannequins in another asylum’s museum – with photos on this blog.

Hospital records (and doctor and nurse interviews) state that Frances was not one of the 300 patients who received a lobotomy. Her attorney, father Ernest, also threatened legal action if the facility dare try any “guinea pig” experiments on his daughter.

The myth that Farmer had been ice pick/lobotomized into a submissive zombie came from Seattle author William Arnold who wrote his Frances bio Shadowland with a Scientologist’s anti-psychiatry agenda. His “fictionalized” story was admitted in court after he sued Mel Brooks’ Production Company for plagiarizing his book for their screenplay of FRANCES (1982). The film poster’s tagline read: Her story is shocking, disturbing, compelling, and true. (well, TRUE- ish)

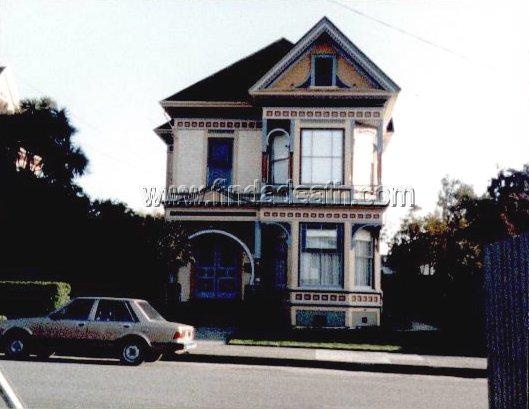

Frances was paroled on March 23, 1950 and returned to her mother’s care. She took a job as laundress at the downtown Seattle hotel that had once hosted her world premiere party of Come and Get It. With her legal rights restored by 1953, Frances must have grown impatient with waiting around for her elderly mother to die and she moved to Eureka, CA. There she lived in this boarding house (with her suitcase full of vodka chained to the metal bed)

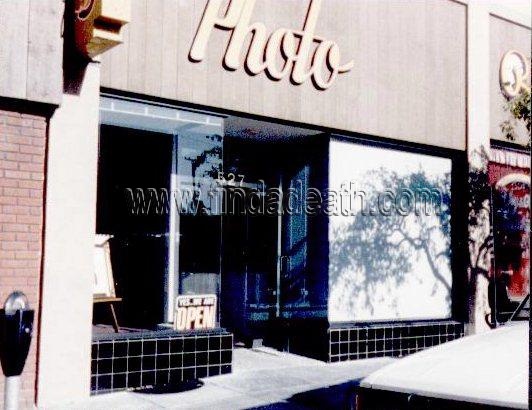

and worked as typist and assistant at this photo shop under the alias Phyllis Anderson.

She had two short-lived marriages in the mid 1950s and the second guy tried to get her on the comeback trail. Neither the marriages or Hollywood comeback worked out. Frances appeared twice on The Ed Sullivan Show, and in a CBS Playhouse 90 teleplay. She also did the 1958 live episode of This Is Your Life (broadcast from the Pantages Theater) where she was presented with an Edsel car for all her televised mortification. On the show, she was harangued by host Ralph Edwards about her rumored alcoholism and nervous breakdown.

Trivia: Appearing on TIYL was one of Frances’s former Seattle acting chums, Jane Rose. Mrs. Rose would become known on television as Cloris Leachman’s mother-in-law on the 1975 sitcom Phyllis.

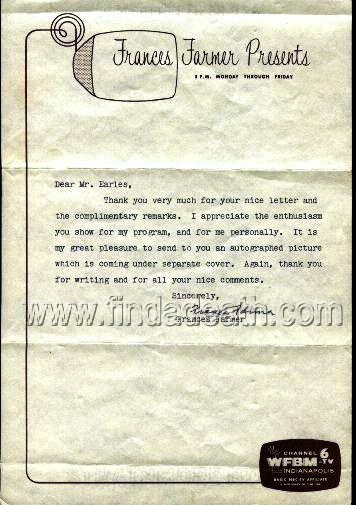

From 1958 to 1964, Frances Farmer hosted an Indianapolis TV show on WFBM-TV called Frances Farmer Presents. Frances did extensive research on the films that she presented and discussed in her live segments. She proved to be an elegant, gracious host and insightful interviewer of visiting celebrities such as Dan Blocker, Vivian Vance, and her own ex-husband Leif Erickson. The show aired 6-days a week and remained #1 in the timeslot for its entire run.

Find a Death friend, Jack Randall Earles of Indianapolis, was a fan of the program when he was in junior high and received a lovely letter and photo from Frances.

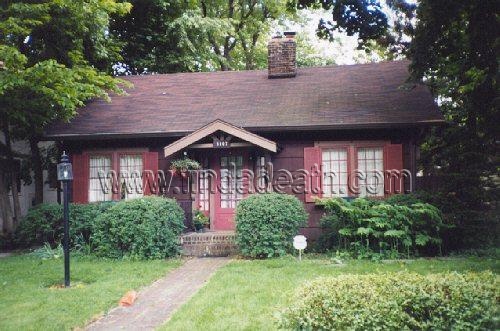

She lived in this home on North Park during her time as TV host. When her Edsel wouldn’t start, she would call her favorite taxi driver, Mike, to take her to and from WFBM-TV studios on N. Meridian Street. At home, Frances would ask him in for a drink which he usually declined. Frances’ secretary said that the only thing you would find in her refrigerator was vodka, beer and dog food.

Frances became actress-in-residence at Purdue University and worked on many productions with students through 1965. She also became a Catholic and was a champion bowler on the Ladies League of St. Joan of Arc Church. She drank a lot of beer and smoked Kent cigarettes. I want to bowl with Frances Farmer.

She was arrested for drunk driving in October 1965 not long after a stressful appearance on NBC’s The Today Show where she was once again asked about her mental illness on national TV.

Locals tell the story of the time Judy Garland rolled through Indianapolis on Oct. 1967 and Frances went to see her show at Clowes Hall. OMG. Backstage. Fly. Wall. Pay lots of money.

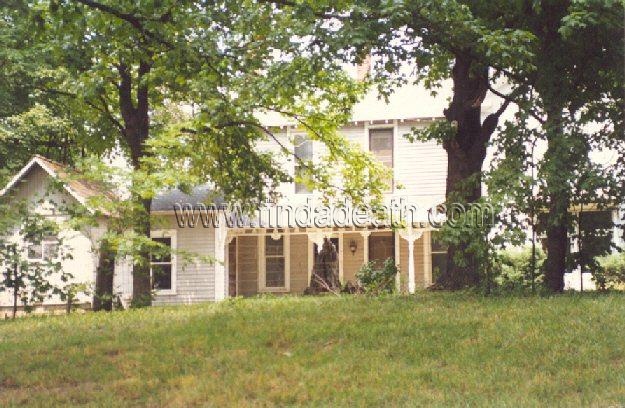

In her final years, Frances and her lady friend, Jean Ratcliffe (with whom she attempted two failed businesses), lived in this home on Moller Road (which has since been replaced with a strip mall).

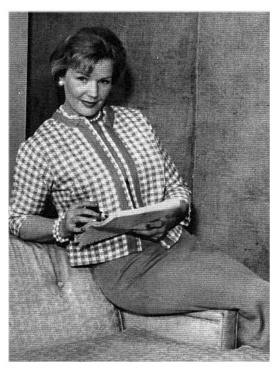

This photo of Frances was taken in 1968.

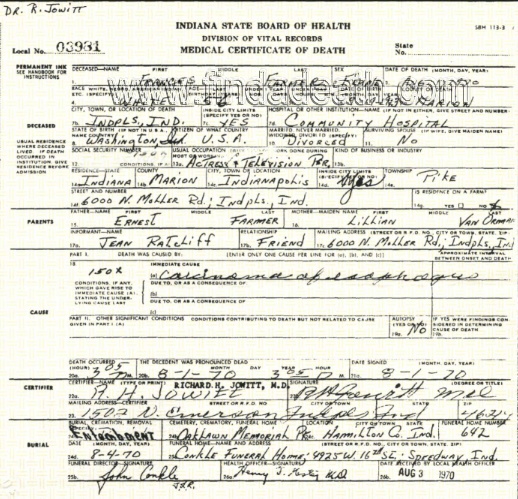

It was while living on Moller Road that Frances lost her battle with throat cancer on August 1, 1970. She was 56 years old.

She is interred in the mortuary at the Oaklawn Memorial Gardens Cemetery. Her pallbearers were six female friends.

(photos courtesy of Scott Durr)

Jean Ratcliffe finished writing Frances Farmer’s autobiography that was published with the title: Will There Really Be A Morning? The book was filled with histrionic family scenes and detailed Jean’s devotion and how she and Frances were not lesbians.

Twelve years later, Frances Farmer would be back in the limelight as the subject of a major motion picture that according to its director, Graeme Clifford, didn’t want to nickel and dime people to death with facts. No stranger to fantasy, Graeme was the film editor on The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain, also from Washington State, sang about Frances in his 90s song: Frances Farmer Will Have Her Revenge On Seattle.

Find a Death Friend CC sends this: Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love named their daughter Frances Bean. Both Kurt and Courtney really loved Frances and Courtney even wore one of her white dresses when they got married in Hawaii.

Michihunt tells me that Frances’ favorite fruit was avocado.

Special Thanks to Jack Randall Earles for his generous contribution of personal photos and Indianapolis information, and Gary Greiner for official documents.

I love Frances. She was tough. She was hounded by people who just wanted the dirt and didn’t care about her feelings and what she went through at all. With the exception of a few friends who truly did care, The world had thrown her away. Rest in peace Frances.